Cats tend to be simple, elegant drinkers. Dogs are not. At a recent summit on fluid dynamics, researchers explain why, with charming video footage to help.

Cats tend to be simple, elegant drinkers. Dogs are not.

At a recent summit on fluid dynamics, researchers from Virginia Tech and Purdue tried to explain why, with charming video footage to help.

Cats and dogs both lap up liquids with their tongues, but new research describes in detail why dogs are inherently sloppier drinkers.

The findings also help to explain why large, hefty dogs produce more backsplash mess than tinier ones. This and more related info was discussed today during the presentation “How dogs drink water,” made at the American Physical Society’s Division of Fluid Dynamics Meeting held in San Francisco.

If the topic seems familiar, it’s because the research team has been analyzing pet drinking habits for a while.

“Three years ago, we studied how cats drink,” Sunny Jung, an assistant professor at Virginia Tech, said in a press release. “I was curious about how dogs drink, because cats and dogs are everywhere.”

Both cats and dogs cannot suck in liquids as humans can because their cheeks facilitate the lifestyle of a four-legged predator. Dogs are omnivores, but their wolf ancestors predominately prey on hoofed animals such as deer, moose, elk and caribou.

The prior research found that felines drink via a two-part process consisting of an elegant plunge and pull, in which a cat gently places its tongue on the water’s surface and then rapidly withdraws it, creating a column of water underneath the cat’s retracting tongue.

“When we started this project, we thought that dogs drink similarly to cats,” Jung said. “But it turns out that it’s different, because dogs smash their tongues on the water surface—they make lots of splashing — but a cat never does that.”

Jung and colleagues determined that when dogs withdraw their tongue from water, they create a significant amount of acceleration — roughly five times that of gravity — that creates the water columns, which feed up into their mouths.

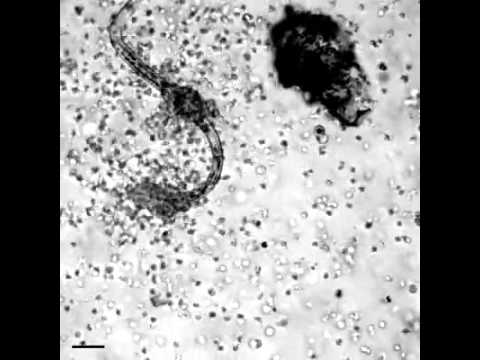

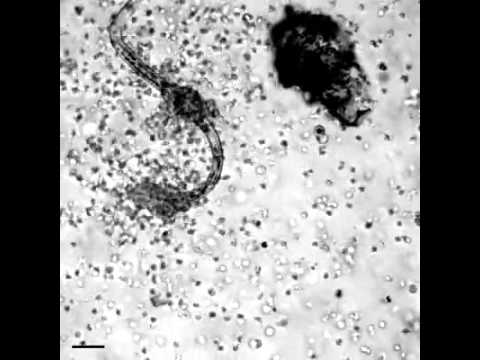

To model this, Jung placed cameras under the surface of a water trough to map the total surface area of the dogs’ tongues that splashed down when drinking.

The researchers found that heavier dogs drink water with the larger wetted area of the tongue. This indicates that a proportional relationship exists between water contact area of the dog’s tongue and body weight, thus the volume of water a dog’s tongue can move increases exponentially relative to the dog’s body size.

The ladle-like canine tongue tip, when full of water, also requires that the dog must open its mouth more to take in the liquid. This further contributes to the splish-splashing.

Jung and his team could only go so far watching dogs drink to determine the underlying physiology. They had to have the ability to alter the parameters and see how they affected this ability. Since they could not actually alter a dog in any way, they turned to models of the dog’s tongue and mouth.

“We needed to make some kind of physical system,” Jung explained.

For their model, Jung and his colleagues used glass tubes to simulate a dog’s tongue. This allowed them to mimic the acceleration and column formation during the exit process. They then measured the volume of water withdrawn. They found that the column of water pinches off and detaches from the bowl of water, primarily due to gravity.

A dog will close its mouth just before the water column collapses back to the bowl.

Jung and his colleagues are now investigating the diving dynamics of plunging seabirds, the skittering motion of frogs and what happens to leaves when they respond to high-speed raindrops. Such findings are leading to a better understanding of fundamental properties of fluid dynamics that can be applied to technological advancements in everything from medical equipment to manufacturing machinery.